One of my seasonal pleasures for many years has been visiting Neal’s Yard Dairy in the autumn months on a quest to buy not just farmhouse cheese but also beautiful, flavourful apples with unfamiliar, evocative names like Blenheim Orange, William Crump or Adam’s Permain, sourced from the Brogdale Collections in Kent.

Brogdale apples

Britain has a rich apple heritage. Shopping at a supermarket though, sadly, one would never know, since even in apple season just a handful of varieties – often imported – dominate. In contrast, Brogdale Collection’s precious orchard, which are home to the National Fruit Collections, grow and maintain over 2,200 varieties of apple trees. Sky Cracknell and Kai Knutsen of England Preserves have long had a special relationship with Brogdale, to whom they were introduced by their friend and mentor the late Brian Haw of the Academy of Fruit and from where they have sourced fruit for their own jams and apple butters.

After Brian’s sudden and sad death a number of years ago, they took on his middleman role of visiting the orchards to select orchard fruit and supplying them directly to a select handful of London food shops including La Fromagerie and Neal’s Yard Dairy. “We were initiated into the process,” explains Sky. “We’d get up very early and drive down there and the manager showed us into the cold rooms where there were all these apples. We’d be there with our penknives, cutting and tasting them. They have such particular and different flavours and textures. Pitmaston Pineapple – that’s my favourite. It tastes of pineapple, which is just the craziest thing, and it’s so beautifully small. I just want every child to have a chance to hold one of them in their hands.”

Sky Cracknell visiting Brogdale to choose heritage apples

This year, in order to support Brogdale’s important educational work, England Preserves are selling its heritage apples both through a click and collect scheme at London’s Spa Terminus and by mail order. The latter was a recent initiative which, especially in these coronavirus times, makes the apples widely available. “I was packing some of our jam and thought I’d give it a go with the apples, so sent a box of them to my parents. My mum rang up, very surprised, and said ‘ooh they’re lovely and they’re all perfect.’” Much to Sky’s delight, she is now sending pallets of apples up each week to Iain Mellis, the renowned Edinburgh cheesemongers. She is on a mission to get people to appreciate heritage apples. “Can you imagine a world where the only flower you saw for sale was a daffodil? Most people understand that they enjoy looking at a whole variety of flowers, but when it comes to apples, they just don’t see it that way.” For Sky, it’s important that these heritage apple varieties should be actively enjoyed. “As far as I’m concerned, if you’re not eating an apple variety, it might as well be dead,” she says emphatically.

When it comes to cooking with apples, I often turn for inspiration to Anja Dunk’s beautiful Strudel, Noodles and Dumplings, a cookbook as comforting as its title suggests. “It’s probably the first fruit I ate,” reflects Anja. “My parents had a small apple orchard in their garden, so I grew up with Russets, Bramleys, Cox’s Orange Pippins. Climbing an apple tree is a childhood memory. If you’re lucky enough to have one in your garden, it’s the most magical thing. I remember taking our apples in my lunch box to school and my friends asking me if they could buy them off me for 10p an apple!”

In the kitchen Anja is inspired by her German heritage. “There are so many German recipes that use apples, with strudel being a very obvious one. Then there’s apfelmus, which is basically apple sauce and gets served with lots of different things. In Germany, bottling is the prevalent way of preserving and it’s such a good way of keeping apples. We’ve got jars of the stuff on our shelves.” When it comes to cooking with apples, she enjoys using them in savoury recipes, with her cookbook containing a recipe for a savoury baked apple rather than the usual sweet version. “We don’t use fruit in savoury dishes enough, I think. There’s a recipe for dotsch– a potato rosti of sorts – which we serve with apfelmus. Potatoes and apples go so well together and they are ripe at the same time of year. Himmel und Erde – Heaven and Earth – potatoes from the soil, apples from the sky, such a lovely creamy combination. Farm food really. Apple is also good with onions. Fried liver with onions and fried apple is fantastic.” Anja’s own children know the pleasures of watching apples grow and eating them from her two apples trees on her allotment. “I think the first fruit I fed my children was apple in the form of apfelmus,” she muses. “A is for apple – it’s so symbolic for children, as it’s the first letter of the alphabet and we’ve all learnt it as that.”

Anja Dunk’s Savoury Baked Apples

Kimpton Apple Press apple juice

As well as being edible, apples can also be pressed and turned into apple juice. Virginia and Henry Clarke’s Kimpton Apple Press, near Andover, Hampshire, offers an apple juicing service that is proving particularly popular this year. “We make sure that people get the juice from their own apples back,” explains Virginia, “which certainly adds to the work, but it’s very satisfying for people who get terribly excited when they collect their bottles. The colours really vary from pale green to pink, depending on the varieties. I always advise people to mix their varieties, as that way you get a really nice juice. We add a little Vitamin C to help the juice keep its colour.”

Customers range from individuals to families through to charities and schools. “It’s a real community thing. A village will pick all their apples together and come or the parents at a school will band together. When people collect their bottles from the barn, there is a harvest feel to it.” The leftover apple pulp is put in the muck-spreader and spread over the Clarkes’ fields to feed birds and mice. “There’s something strangely satisfying about getting the apples and going through this process,” Virginia observes. “If you’ve got too many apples to eat, this is a good way to keep them. We’re all coming to understand that we’ve got to make the most of our resources. During lockdown, we drank our own apple juice, gave it to neighbours, gave it to foodbanks. There’s a cleanness to it because you know it’s comes from your own fresh fruit that were growing on your tree.”

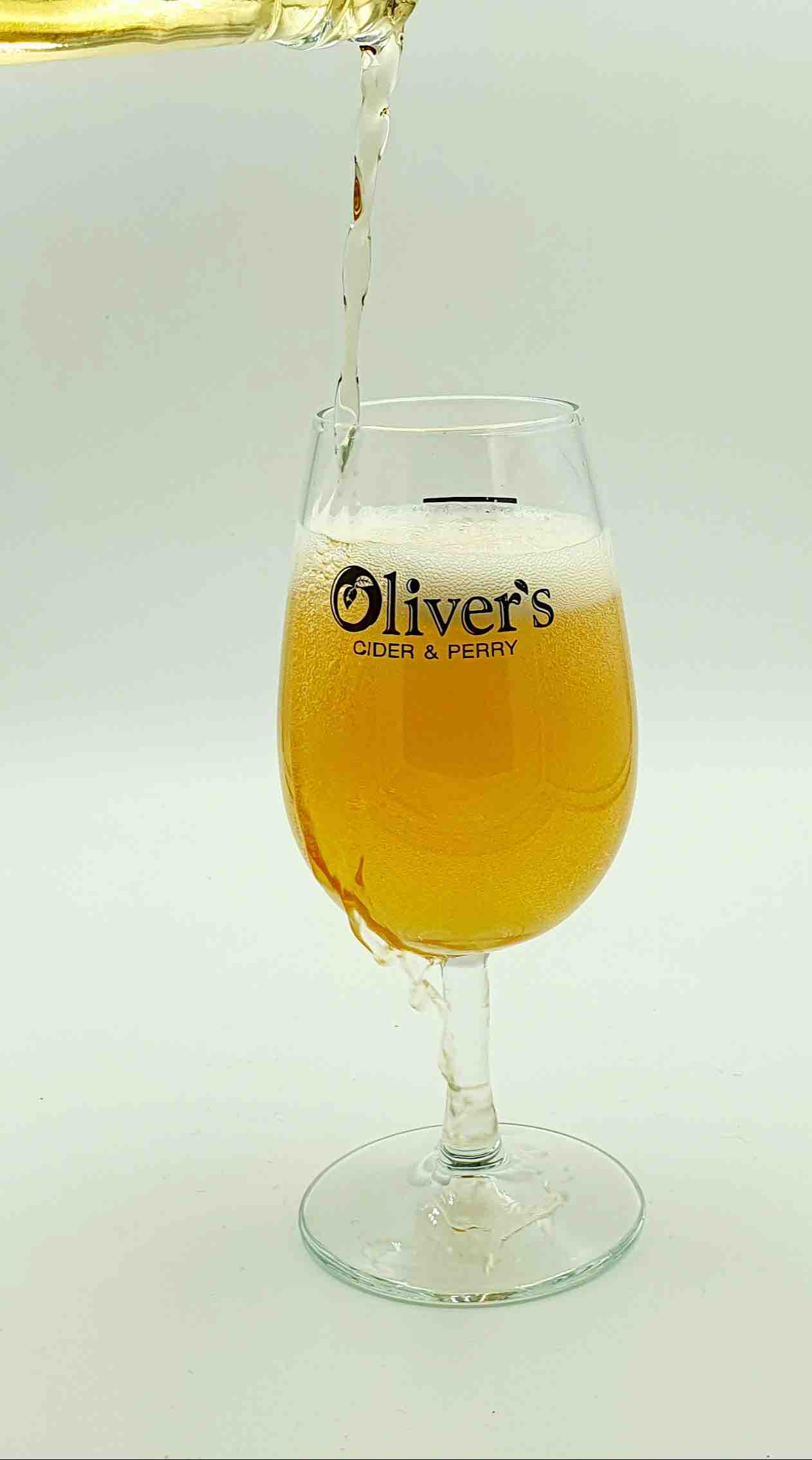

By fermenting apple juice, of course, one can turn it into cider, a drink which has been made for centuries in Britain. “Cider was made on my grandfather’s farm as a drink for the workers,” explains Herefordshire cider maker Tom Oliver of Oliver’s Cider and Perry. “It was part of the tradition locally to offer them watered down cider – ciderkin – as refreshment.” While economic pressures saw his grandfather shift to growing hops rather than cider apples, Tom’s personal fascination with cider saw him set about making it himself. “I am a cider drinker. I really love it. As my palate developed, I started to understand that cider could be a really fantastic drink. I sensed that there were not many people aiming for the heights. It had been reduced to a really poor shadow of its former self, which was one of the spurs for me thinking I could make a good go at this. The making and selling has been for 22 years, but I was planting trees for maybe the previous ten years before that.”

Cider apples

In the pre-Internet era when he started planting, sourcing cider apple trees and finding information on how to grow them was “quite a struggle”. Over the years, the traditional standard orchards have been replaced with bush orchards, which come into fruit earlier, are easier to spray and manage and can be harvested mechanically. “A lot of the old traditional cider apple varieties were lost, because these bush orchards concentrated on, let’s say, a dozen varieties, whereas there were 200 varieties at least in common usage in Herefordshire.” As the ability to DNA test has become more affordable, “a lot of progress has been made identifying trees – it’s very exciting.” What differentiates cider apples – such as Dabinett, Foxwhelp, White Beech or Yarlington Mill – from eating apples is their high tannins. “You can get a cider apple that eats like a combination of a dry cracker and a dry teabag! These tannins not only give you this incredible mouthfeel and astringency, they have anti-oxidative and anti-microbial properties to give you a cider that keeps well.” Given the potential pitfalls that fruit farmers face – pests, disease, frosts, plus the fact that many cider apples only crop every other year – Tom only grows 10% of the fruit he uses, so as to spread the risks and ensure supply.

At this time of year, Tom and his team are busy harvesting, collecting and pressing cider apples, a process which carries on into early December. The apple juice is pumped into containers and once it begins the process of spontaneous fermentation – “we don’t add nutrients or sulphur before fermentation” – it is left well alone until April or May. “Some people are inveterate fiddlers. I’m an inveterate hands off,” says Tom firmly. The process is not without its potential problems, he explains; “With wild, spontaneous fermentations there’s always an element of risk. There’s no way of governing it.” One danger is the development of “off flavours – there’s one horrible one called ‘mouse’ which tastes like the bottom of a mouse cage”. After the wait, tasting the fermented juices in April or May is exciting. “My cider making is not science-based, it’s taste based. At this stage, it’s still not a finished story, so what I’m interested in is its potential. It might need some maturing, or to go into oak or blending to bring out the best of it. In the way that wine vintages vary, my ciders mirror the season and what we can get out of the apples that particular year.” Time plays an important part in creating his ciders. “It can take six to eight months, but more like ten; some are matured for up to 18 months. I have bottled conditioned ciders which I release as and when they’re ready. I have some from 2017.”

Barrel ferment, Oliver’s Cider

Tom’s knowledge and skill at cider-making has found an appreciative audience. “Finally! It’s the thing that’s heartened me most, after getting on for nearly 25 years of suggesting to people that cider can be a really fine drink, that it’s not just what you see at the supermarket checkout. It’s capable of holding its own at the table, accompanying food, has got some wonderful character. The thing we hear time and time again from younger drinkers is ‘we had no idea that cider like this existed’.”